This essay won the competition in its first year. In its original length it was nearly 3,500 words and we have cut two paragraphs to reduce it to 3,000 words. In future years we recommend a length of 2-3,000 words, so that students are not wondering about how much to write.

One of the reasons why the Panel at the Historian judging essays were delighted with it, is that the student did not just repeat information on this website or from other sources, but developed her own thoughts about Petit and why he is interesting to study today.

What impact has Petit had to help shape our understanding of Victorian life and culture?

Tiffany I, Y10, A South London School

Rev John Louis Petit (1801-1868) created thousands of paintings during the 1800’s, many of which were of ecclesiological architecture and helped to portray the damaging effects of the gothic revival – a movement Petit appeared to oppose. During the 1840’s Petit’s artwork started to change and adopt many features of the impressionist paintings that became popular decades later. The industrial revolution greatly impacted life during the Victorian era and this is also evident in some of Petit’s paintings. In many ways, Petit was an activist and although his artwork remained hidden and has received little attention, his messages are rich and loud – provoking thoughts about subjects that are equally relevant today.

The gothic revival and renovation of St Mary’s

An architectural, artistic and religious movement that was rapidly gaining popularity during the mid 1800’s was the gothic revival, competing with the popular neo-classical style. It was common for scholars to study theology at university and many often became clergymen and worked with churches so debates about church architecture were heatedly discussed. Societies such as the ecclesiologists (Cambridge Camden Society) soon emerged. The ecclesiologists were a group of scholars who had been brought together and led by John Mason Neale in 1839. The group were avid followers of the restoration of gothic architecture specifically “decorated gothic” – a style that was popular in medieval architecture in the UK, during the years 1270-1370. As the name suggests, the ecclesiologists’focus was on church buildings and they passionately argued that the only suitable way to design a church was in the decorated gothic style and they heavily contested those who disagreed with them. Neale and the other members of his group admired the work and certain doctrines of Augustus Pugin. Although he was not heavily involved in the debates himself, Pugin’s writing on architecture and the buildings he designed were incredibly influential.

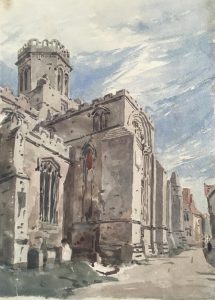

Some took this a step further and a form of destructive revivalism emerged and gained pace and influence in the 1840’s. The belief that only a specific type of gothic style should be used to design churches was formed into a strict set of rules and structures that did not conform to these rules were set out to be renovated or, if that was not possible, destroyed. The main drivers behind this movement were members of the ecclesiologists who wanted more control and power in the debate. Petit published Remarks on church architecture in 1841 with the intention of bringing the beauty of non-gothic churches and the dangers of destructive revivalism to light. Many of his illustrations and studies of ecclesiological structures are included in this to support his arguments. One church that Petit seems to have fought particularly hard for was St Mary’s, Stafford. The church itself was a deeply historical building with a rich past – located in a town that was once the center for trading and the military of its region before the Norman conquest. George Gilbert Scott was a significant gothic revivalist responsible for designing and altering over 800 buildings during his lifetime. He drew inspiration from Pugin and together with the ecclesiologists he altered many cathedrals and churches in order to make them conform to a gothic style. Sometimes these buildings were already in ruins but many, including Petit, believed that they had become important artifacts that needed to be preserved rather than changed. In the years leading up to 1843, Scott and Petit campaigned and debated about what ought to be done with St Mary’s. The revivalists believed that a sloping roof needed to be constructed however Petit disagreed. He argued that the original roof provided the church with character and uniqueness and that changing that was unnecessary. Because Petit campaigned so heavily for the preservation of St Mary’s he produced a large number of paintings and these really do capture its character and personality. They serve as important documentation on the nature of the church before its reconstruction and allow us to gain insight into whether these changes were needed. Petit captured the church from many different locations around Stafford and with many different perspectives. Although he lost this particular “battle”, his enthusiasm and efforts were not in vain. Later in life, Scott went on to agree with Petit regarding the unneeded renovation and Petit’s views on preservation serve as an important reminder for our duty and responsibility to look after and appreciate not only architecture but nature and art, his message can be interpreted universally. His detail in recording the churches before they were renovated or destroyed act as important pieces of evidence that are needed to understand how architecture has changed.

St Mary’s Stafford, 1843, John Louis Petit (JLP) – sourced from Petit’s tours of old Staffordshire

There is a lot more information and focus on architects such as Pugin and Scott and this focus is deserved and understandable – they created many incredible structures and important pieces of literature, but this does not justify the dismissal of Petit’s work. In my opinion, Pugin was more of an independent thinker as he was an early influencer and driver of the movement. His focus seemed to be on the architecture rather than on power and dominance. Groups like the Cambridge Camden society seem to have strayed away from Pugin’s appreciation for architecture and individualism. Petit recognized the dangers of imitation and creating churches that looked too similar to each other as this created a lack of authenticity and what he believed to be a closeness to God. Petit’s views and methods of recording provide an alternative perspective to what is commonly seen and helps to create a more well-balanced and exciting image of how issues affecting Victorians were dealt with. I feel as though both Petit and Pugin had an appreciation for intricate details that were overlooked. This is shown through Petit’s dedication to abandoned churches and in his attempts to highlight the beauty in simple things. This painting of some rubble in St Mary’s creates a sense of value, history and authenticity while showcasing the damaging effects of destructive revivalism. Pugin once said that “In pure architecture the smallest detail should have a meaning or purpose”1 and although he was not a gothic revivalist, I feel that Petit has honored this greatly in his work.

Rubble in St Mary’s during renovation, 1843, JLP – sourced from Petit’s Tours of old Staffordshire

Views on Modern Architecture and the crystal palace

As mentioned throughout this essay, the impact and importance of the industrial revolution was immense. It greatly affected the lives of many living in Victorian England and across the world, changing the structure of society itself. Therefore, it is only natural to expect the numerous changes in architecture that came about as a result. Industrialization meant that building projects could be completed more efficiently with the use of machines and transport systems such as trains. Materials such as glass and iron were easier to obtain and the removal of Glass duty (1845) , Brick duty (1850) and Window tax (1851) allowed for cheaper production of buildings with these features. There was a subsequent increase in “modern” buildings that made use of the repealed taxes and created structures that were not seen before. An infamous example of this was the Great Exhibition of 1851. Designed by Joseph Paxton this state-of-the-art building was mainly constructed of cast iron and plate glass (making the building incredibly affordable) and was an example of the emerging greenhouse style buildings that utilized newer and cheaper methods of glass and iron production. Other examples of these are Palm House, Kew gardens (1844) and Chatsworth Conservatory (1837) – the latter designed by Paxton. The difference between these and the Great Exhibition was the magnitude of the building. There had never been a glass house of such a scale – 990,000 square feet . Six million people visited it during the 5 months it was open and this would have been equivalent to around one third of the British population during the 19th century. It was unusual for a building to have so many visitors in such a short period of time, adding to its notoriety.

The building itself was temporary, built as a showcase of some of the British empire’s most incredible possessions – perhaps with the intention of showing the world its power, influence and leading role in industrialization. It contained over “100,000 objects”2 ,ranging from machinery to fine art. The building represented prosperity and achievement but also signaled at the hopes and possibilities of the future. For many this glass building provided a glimpse at the future of humankind and acted as a reward; an opportunity for industrial pride to take over. The great exhibition received a lot of attention from the media and was dubbed the “crystal palace” due to its use of glass. Despite its popularity, the great exhibition was still subject to opprobrium and was “called a “glass monster”by one critic and a “magnified” conservatory by another” 3 .

The building was deconstructed in 1851, originally intended as a temporary exhibition. Regardless of this, it was not forgotten and since it had been such a great success it was permanently reconstructed. The location chosen was at one of the highest points in Sydenham – in a park now known as Crystal Palace Park, named after the glass building it housed. Unlike its predecessor, the crystal palace’s success was slight and the building quickly fell into a state of neglect and deterioration. Only a few years after it was built it had faded out of significance. It may be that the building was destined to be momentary and short lived – its original temporary nature destinated to prevail. Mysticism aside, the crystal palace burned down in 1936 and all that remains are scattered pillars and a vast expanse of grass, its former scale hauntingly apparent under the gaping absence it has created.

Petit created two paintings of the crystal palace, each having a slightly different tone and character to it. A friend of his, Phillip Delamotte, was a keen photographer and he produced a series of photographs of the crystal palace. Because of its notoriety many photographs, paintings and sketches were created of the crystal palace and as a symbol of modernity it was understandably subject to hundreds of opinions and perspectives. These provide us with insight into attitudes regarding a plethora of issues prevalent in the 1800’s.

Petit’s Crystal Palace:

“Syndenham”, John Louis Petit (estimated creation 1854)

The painting above shows the crystal palace in the background with trees and a landscape in the foreground. This painting achieves a sense of the palace’s magnitude and scale. By placing the palace in the background, a sense of respect is created as the palace seems to watch over the elements in the foreground and although this was unintentional as the glasshouse burned down 68 years after Petit passed away, the faint nature of the building hints at its transience. While a sense of its might and awe is created, the red hue that stains the page could symbolize a subtle anger toward industrialization Petit may have felt (this may not be the case as this hue features in some of his ecclesiological paintings) Red and green are contrasting colors so this pairing could show the contrast between man and nature. The size of the crystal palace could show man’s overpowering of nature but contrarily, the harmony and balance in the composition of the painting could show how man and nature co-exist.

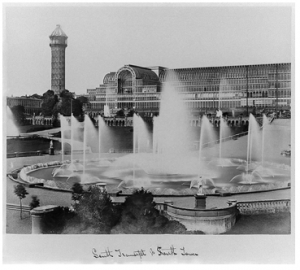

By choosing this angle to paint from, placing nature in front of the crystal palace, Petit was able to highlight the permanence of nature and its history, which is juxtaposed by the modernity and infancy of the industrial revolution and its products. Compared to a photograph by Philip Delamotte, the character created by the painting is unique and personal, capturing a range of emotions the camera couldn’t but sacrificing the accuracy and detail only a photographer can achieve. The photograph below seems more sterile and while it shows the scale and power of the crystal palace, it can feel bleak and fanciful – lacking the emotion of Petit’s painting.

The fountains at the crystal palace, Phillip Delamotte, National Monuments Record – English Heritage. Collection created between 1852 and 1859.

Note: information about the paintings and photographs of the crystal palace provide little clarity about the exact date –so the studies could be from 1851 or the reconstruction. However, the general structure of the building remains the same so comparisons can be drawn regardless.

Before analyzing Petit’s second painting of the crystal palace, it is important to note that during this time Petit’s painting style had drastically changed and was becoming more impressionistic. It is also important to note that Petit was not a commercial artist. He was not commissioned. He painted for observation; he painted to show his love for architecture and he painted to capture the essence of a building.

Petit’s painting (left) feels like a sketch. It’s lack of strong shapes and outlines of trees and people are similar to the impressionist style that emerged in the 1860’s, around ten years after this was painted. The walls and ceiling of the palace seem much larger than the trees creating a sense of scale. The painting highlights the shapes used in the building and make it easy to create connections between the crystal palace and other buildings such as train stations, particularly St Pancreas international and its glass roof. The “modern” style of architecture is clear and distinct and different from Petit’s paintings of churches.

A commercial illustration (right) has a different atmosphere and tone to Petit’s painting. It is clear that both pieces of artwork are of the same building, granted they are of different parts of it. The commercial piece exudes grandiose and luxury, both of which are elements of the great exhibition’s image and portrayal in the media. By comparing both pieces of artwork, it is clear that Petit’s has more of a focus on the structure of the building and its architecture whereas the commercial image is more focused on cultural significance and appeal. The photograph below provides some structural detail, however it also focuses on the contents of the crystal palace. All three show us that the crystal palace housed plants, many of which are now known to have been exotic, which add to the functionality of the building as a glass house.

The significance of the crystal palace provides insight into how important architecture was and celebrates the positive aspects of industrialization. When paired with the information about the gothic revival it becomes easy to see just how diverse architecture is and how views about society, the industrial revolution and religion affect these buildings. As Petit was an advocate for creativity and forward thinking in architecture it does not come as a surprise that he would observe and study the great exhibition. Although he only created two studies that I am aware of, they do a wonderful job at capturing the personality, size and structure of the crystal palace, especially when paired with historical context. Seeing these images is crucial to developing our understanding of Victorian life since they are sources form that time period but also as the crystal palace, like so many other structures Petit painted, have been destroyed by the test of time and no longer stand for observation. When presented with a wide range of images and buildings, it becomes easier to create a more accurate and diverse view of developments in architecture and societal values because buildings are heavily influenced by and therefore reflect those values.

Conclusion

If this essay has achieved the purpose I intended, you should leave secure with the knowledge that Petit’s work has had a rather substantial impact on bettering our understanding of life and culture during the 1800’s. His artwork provides us with primary sources, detailing structures that no longer exist, his books provide us with information about cultural and religious ideas regarding architecture and his evolving style can be placed among the shifting artistic climate of the Victorian era. Petit’s work alone does not provide us with everything we need to know but once it is paired with research and the works of other great minds, a comprehensive picture of life 150 or so years ago is created.

By looking at Petit’s artwork I was inspired to research further into the reasoning behind them and I landed right in the middle of an important cultural debate. Petit’s painting of the crystal palace, which is less than a 5-minute walk from my school, provided more perspective into the matter and made me realize the significance of what is no longer seen. The world is continuously changing and nothing is constant, so artists like Petit are crucial for preserving history. Before the widespread use of cameras, it was up to artists to decide how and what they recorded. Petit’s work was unusual for his time and by going against the status quo he not only reflected the subversive culture that was rising but reminds us that we need to do the same. It is all too easy to fall into the trap of conventionality and succumb to the accepted way of doing things. Currently, we have many issues to stand up for, regarding preservation and beyond. Seeing Petit refuse to accept the destruction of what he loved should act as an inspiration for people nowadays. Although unsung for many years, I hope that more information surfaces and that his work reaches more people and receives the praise it deserves.

References:

1 – The true principles of pointed or Christian architecture (ed. 1853)

2 – Buildings across time, 4th edition, chapter fourteen

3 – https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/dickinsons-comprehensive-pictures-of-the-great-exhibition-of-1851

General information:

Petit’s tours of old Staffordshire – Phillip Modiano

Remarks on church architecture – John Louis Petit

The 7 lamps of architecture – John Ruskin

English Heritage webpage and multiple documentaries and webpages (please contact me if this information is required)